The northern limits of the city of Guadalajara are clearly defined by the beautiful but nauseatingly smelly and polluted Santiago River, which flows through the dramatic Barranca de Oblatos canyon and its sheer walls that are 500 meters deep.

What lies on the other side of that challenging chasm?

“To some, it may look bleak over here,” says ranchero Salvador Mayorga, “but in reality, the ecosystem is fascinating. This is the habitat of wild boars, pumas, armadillos, black iguanas, white-tailed deer, wild turkeys, parakeets and an infinite variety of invertebrates.”

It’s also the perfect place to view the Barranca in all its glory, as I discovered when I camped out at Mayorga’s Rancho el Mexicano, which features no electricity and no internet, and — although it is located only four kilometers from the busy streets of Mexico’s second-largest city — still feels pretty close to the middle of nowhere.

Well, I happened to be visiting Rancho el Mexicano with archaeologist Francisco Sánchez, and when I mentioned the loneliness of our surroundings, he turned to me.

“Would you believe that this desolate mesa we are on was once chosen by the Spaniards as a great spot to found the city of Guadalajara? Not far from here there’s a monument marking the place, and I know right where it is.”

Naturally, my friend Rodrigo and I prevailed upon the archaeologist to show us the historic spot. As we drove along, Francisco explained that the first attempt to found Guadalajara was in Nochistlán in Zacatecas in the year 1532, but there wasn’t enough water and that plan was scuttled.

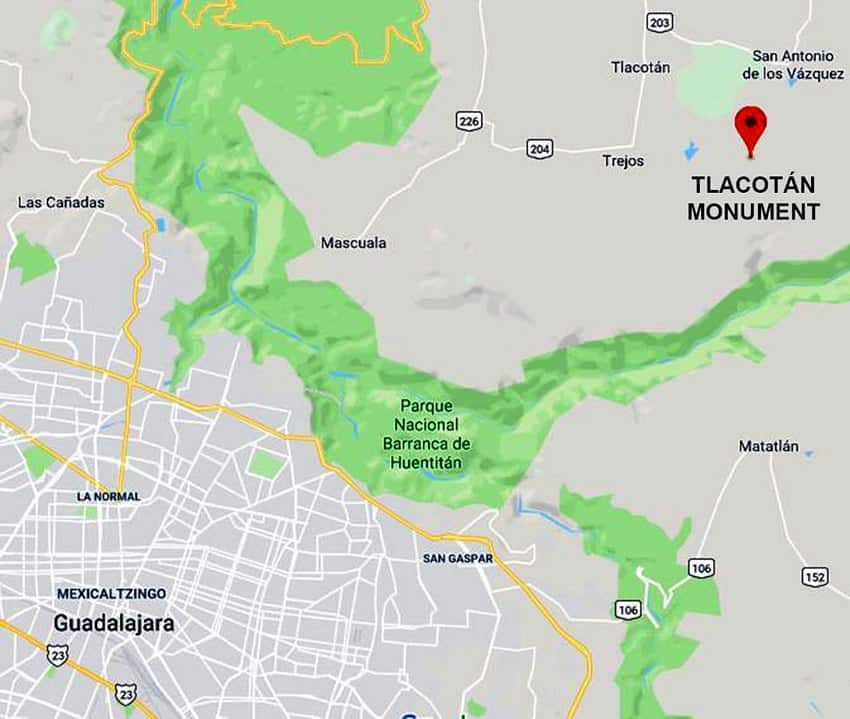

Next they tried Tonalá, but Nuño de Guzmán, the Spanish conquistador and colonial administrator for New Spain, chased them away, saying he wanted that land for himself. Then they decided upon the spot we were heading for, called Tlacotán, located 17 kilometers northeast of today’s Guadalajara Zoo.

Francisco stopped the car. “We’re here. The monument is just a few steps away.”

Well, this place looked even more solitary than Rancho el Mexicano, and I couldn’t see a monument anywhere. However, Rodrigo and I followed Francisco on a winding path through the bush until we came to a barbed-wire fence.

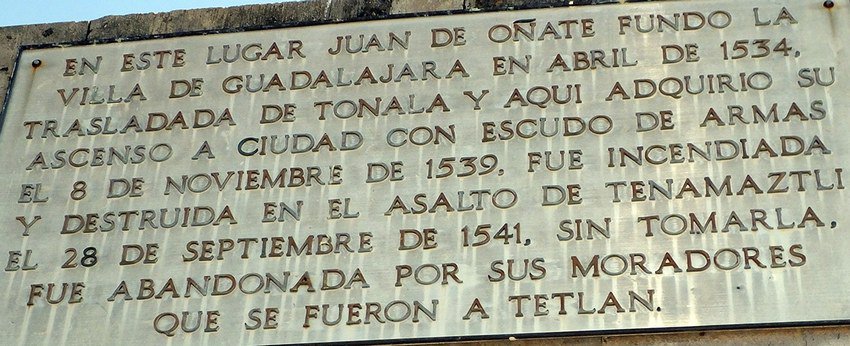

Now, as has been proven again and again, all good adventures in Mexico start with a step over, under or through a barbed-wire fence … and this was no exception. On the other side of the fence was a row of trees, and then we saw it: a great slab looming above us like the monolith in 2001, A Space Odyssey. All around it was nothing but cornfields as far as the eye could see. A big engraving stated that this was the place where the village of Guadalajara was founded in 1535 and where it was declared a city by royal decree in 1539.

“But there’s nothing here! Where are the ruins?” we asked our guide, who assured us that back in those days there were houses, a cathedral and a big plaza shaded by a tall zapote tree.

“So, what happened?” I asked.

“What happened was Tenamaztle, leader of los indígenas Caxcanes, who according to the records of the Spaniards appeared on top of those distant hills on September 27, 1541, with 15,000 men, all of them infuriated by the Spaniards’ custom of enslaving native peoples.

Pedro Plascencia, who happened to be out in that direction collecting firewood, saw them coming down the hills in great waves, but the Spaniards had foreseen the possibility of a big attack and had reinforced one of their houses, erecting towers and walls around it and sealing up all the doors but two in order to protect their little city.

And then they were attacked by thousands of Caxcanes, most of them naked and painted red from head to foot, their skulls shaved except for a ponytail. Some of them wore clothing or armor taken from dead Spaniards, but their only weapons were bows and arrows.

“For four hours the Spaniards fought back with their guns, crossbows and cannons. When it was all over, they say 15,000 Caxcanes lay dead with rivers of blood everywhere, but only two Spaniards had been killed.

“So Cristóbal de Oñate, governor of the city, ordered that the corpses be thrown over the cliffside into the Río Verde Canyon to prevent an epidemic, but all the bodies lying more than two kilometers from the city were left in place as proof of what had happened and a warning to any other native people that might want to attack them.”

The following day, the archaeologist told us, the Spaniards celebrated a Mass, giving thanks for the miracle they claimed had occurred during the battle. They said a man dressed all in white and riding a white horse had appeared in the middle of the fighting, holding a cross in his right hand and a sword in the other. “It was San Miguel,” they said, “and he is the one who killed most of the Indians.”

Saint Michael, however, was not the only hero in that battle. A group of 10 soldiers was in charge of defending one of the doors in the homemade fortress when a huge and powerful Caxcán suddenly burst in, so big that no one dared go even near him.

“In the room,” said Francisco, “was Doña Beatriz Hernández. She was dressed in armor with a machete in her belt. Pulling it out, Beatriz walked right up to the warrior and slashed at his throat. The huge man crashed to the ground, and Beatriz finished him off. This was the moment she got her reputation for being feisty and brave and not letting anyone tell her what to do.”

The next day, all the women and children left Tlacotán with an escort and followed the Camino Real to Tonalá, a journey of at least eight hours. A certain number of Spaniards stayed on, waiting for the arrival of the Viceroy of New Spain, Antonio de Mendoza, with thousands of friendly indígenas who would finish off the rebellious ones.

From Tonalá, soldiers explored the Valle de Atemajac to find a better place to reestablish Guadalajara, and a meeting took place near the present Degollado Theater.

There was much disagreement, and to end it, Cristóbal de Oñate pulled out his knife and drove it into a tree, declaring that this would be the location of the new Guadalajara, in the name of the king. Still, the arguing continued until Doña Beatriz stood up and said, “El rey es mi gallo [I stand by the king — a quote from Don Quijote], and we are staying here for better or for worse!”

“You heard the lady,” said Oñate, and that ended the discussion. And that’s why you’ll find a prominent statue of Beatriz in the very center of Guadalajara, at the southeast corner of the Teatro Degollado.

Should you ever find yourself wandering about the barren mesa north of this city, with nothing much to do, you can easily visit the monument to the third incarnation of Guadalajara by asking Google Maps to take you to “QRRV+GR Trejos, Jalisco.” Don’t let the pandemic stop you: I’m sure it won’t be crowded.

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, for 31 years and is the author of A Guide to West Mexico’s Guachimontones and Surrounding Area and co-author of Outdoors in Western Mexico. More of his writing can be found on his website.